Iranian, German archaeologists in search of clues about Achaemenid, Sassanid miners

TEHRAN – Teams of Iranian and German archaeologists have commenced a new season of excavation on an ancient Iranian mine, which has so far yielded a number of ‘salt mommies’, personal belongings as well as animal remains.

Situated in Zanjan province, Chehrabad (Douzlakh) salt mine has received increasing interest from Iranian and international archeologists. Also, the biological remains from this site have provided valuable sources for studying the pathogenic agents of ancient times.

Led by senior archaeologists Abolfazl Aali and Thomas Stöllner, respectively, the Iranian and German teams aim to gain further strong evidence about the history of mining at Chehrabad salt mine, particularly during the Achaemenid (c. 550 – 330 BC) and Sassanid (224-651 CE) eras, according to the Research Institute for Cultural Heritage and Tourism (RICHT).

Results of previous excavations suggest that Chehrabad has been the subject of a long-term activity that started from the Achaemenid era continuing in different periods including Sassanid, Seljuk, Safavid, Qajar, and Pahlavi periods, ISNA quotes Aali as saying on Saturday.

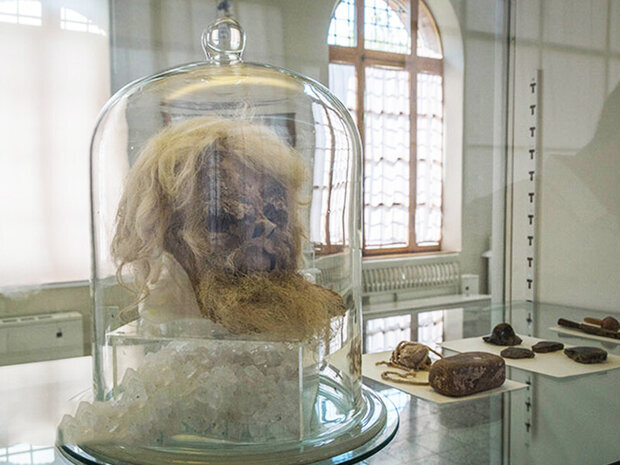

What was a catastrophe for the ancient miners has become a sensation for science. Sporting a long white beard, iron knives, and a single gold earring, the first salt mummy was discovered in 1993. He is estimated to be trapped in the mine in ca. 300 CE. In 2004 another mummy was discovered only 50 feet away, followed by another in 2005 and a “teenage” boy mummy later that year.

“Several miners known today as salt men were trapped, killed, and buried inside the mine in various periods including the Achaemenid, the beginning and end of the Sassanid era, as well as Qajar and Pahlavi periods,” the archaeologist explained.

“Collapses occurred in Chehrabad mine and its extraction tunnels mostly due to the lack of integration of salt veins, earthquakes, and non-observance of safety issues.”

Mummified remains have long attracted interest as a potential source of ancient DNA as such mummification is a rare process that requires an anhydrous environment to rapidly dehydrate and preserve tissue before complete decomposition occurs.

What was a catastrophe for the ancient miners has become a sensation for science. Sporting a long white beard, iron knives, and a single gold earring, the first salt mummy was discovered in 1993.Research on a mummified sheep co-authored by 15 international experts including Aali and Stöllner, has shed new light on sheep husbandry practices of the ancient Near East and underlined how natural mummification can affect DNA degradation.

“We present the whole genome sequences of a ~1600-year-old naturally mummified sheep recovered from Chehrabad, a salt mine. Comparative analyses of published ancient sequences revealed the remarkable DNA integrity of this mummy. Hallmarks of postmortem damage, fragmentation, and hydrolytic deamination, are substantially reduced, likely due to the high salinity of this taphonomic environment. Metagenomic analyses reflect the profound influence of high salt content on decomposition; its microbial profile is predominated by halophilic archaea and bacteria, possibly contributing to the preservation of this sample. Applying population genomic analyses we find consistent clustering of this sheep with Southwest Asian modern breeds, suggesting ancestry continuity. Genotyping of a locus influencing the woolly phenotype showed the existence of an ancestral “hairy” allele in this sheep, consistent with hair fiber imaging, further elucidating Sasanian-period animal husbandry.”

According to the authors of the research, in 1993, a remarkably preserved human body dating to the ~1700 years Before Present (BP) was discovered in the Douzlakh salt mine near Chehrabad village in the Zanjan province of northwest Iran. A total of 8 “Salt Men” have been identified at the mine, several retaining keratinous tissues such as skin, hair, and both endo- and exoparasites, despite dating to the Achaemenid and Sasanian.

Their research proved that the mine was active in various periods and its archaeological refilling layers represent an extraction history that ranged from the 6th century BC to the 20th century CE. In addition to the “Salt Men”, textiles, leather objects, and animal remains have been discovered, likely preserved by the high salinity and low moisture content of the mine.

Furthermore, isotopic, genetic, and lipid analyses have been reported for this material, and studies have been carried out to characterize genomic DNA survival. These human and animal remains are examples of natural mummification - the spontaneous desiccation of soft tissue by a dry environment that rapidly dehydrates soft tissue before decay begins.

Mummification provides scientists significant evidence that bears sufficient keratinized tissue for ancient DNA sequencing. “Mummification has been suggested as a mechanism that may sufficiently preserve keratinized tissue for ancient DNA sequencing. The effects of age-related damage in DNA are well documented and include base misincorporation at strand overhangs, fragmentation, and low endogenous content.”

Both deamination and depurination, associated with postmortem transition error and DNA fragmentation, respectively, require water as a substrate.

As mentioned in the research, ancient DNA from Chehrabad, a highly saline, anhydrous environment, presents an opportunity to investigate potential differences in nucleotide degradation resulting from this unusual taphonomic context.

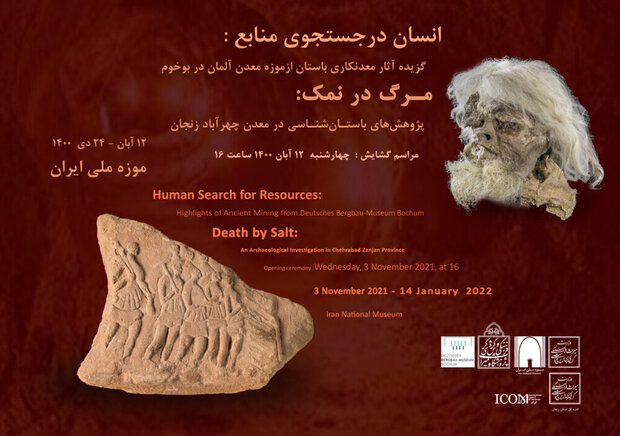

Currently, a special exhibition featuring Iranian and German studies in the realm of ancient mining is underway at the National Museum of Iran in downtown Tehran.

It puts the spotlight on the appropriation of humans to mineral resources and the development of the history of human experiences and achievements in mining, which led to the development of technologies, the formation of professions, trade, and specialization of industries.

"Highlights of Ancient Mining from Deutsches Bergbau-Museum Bochum" and "Death by Salt" are highlights of the event, which will be running through January 14, 2022.

According to Jebrael Nokandeh, the director of the National Museum, the museum and the German Mining Museum in Bochum have made considerable cooperation in line with an agreement they signed in 2017, based on which the two institutions are set to hold exhibitions of each other's historical and cultural artifacts related to the subject of ancient mining.

It is worth mentioning that similar loan exhibitions featuring ancient mining and relevant documents were already staged in Iran and Germany.

Last year, a team of experts from the two countries started a project for purifying, cleansing, and restoring garments and personal belongings of the mummies which were first found in the salt mine in 1993.

The oldest-known mine on archaeological record is believed to be the Ngwenya Mine in Eswatini (Swaziland), which radiocarbon dating shows to be about 43,000 years old. At this site, Paleolithic humans mined hematite to make the red pigment ochre. Moreover, mines of a similar age in Hungary are believed to be sites where Neanderthals may have mined flint for weapons and tools.

AFM

Leave a Comment